What I ended up learning as a result of an offhand comment about Orville Wright not having a pilot's license

This week's "what I learned" started with someone saying offhandedly, "You know, Orville Wright didn't have a pilot's license." The underlying point being that expertise often follows innovation rather than preceding it.

Which lead me to Samuel Langley and the Smithsonian. Which I knew a bit about. And then, Gustave Whitehead and other claims of powered flight before 1903. Suddenly I'm looking at an example of how truth can be stranger than fiction, some about institutional influence, and then fashioning what gets written up in textbooks and laid down as true history.

Okay, let's go back in time.

The original venture-backed moonshot

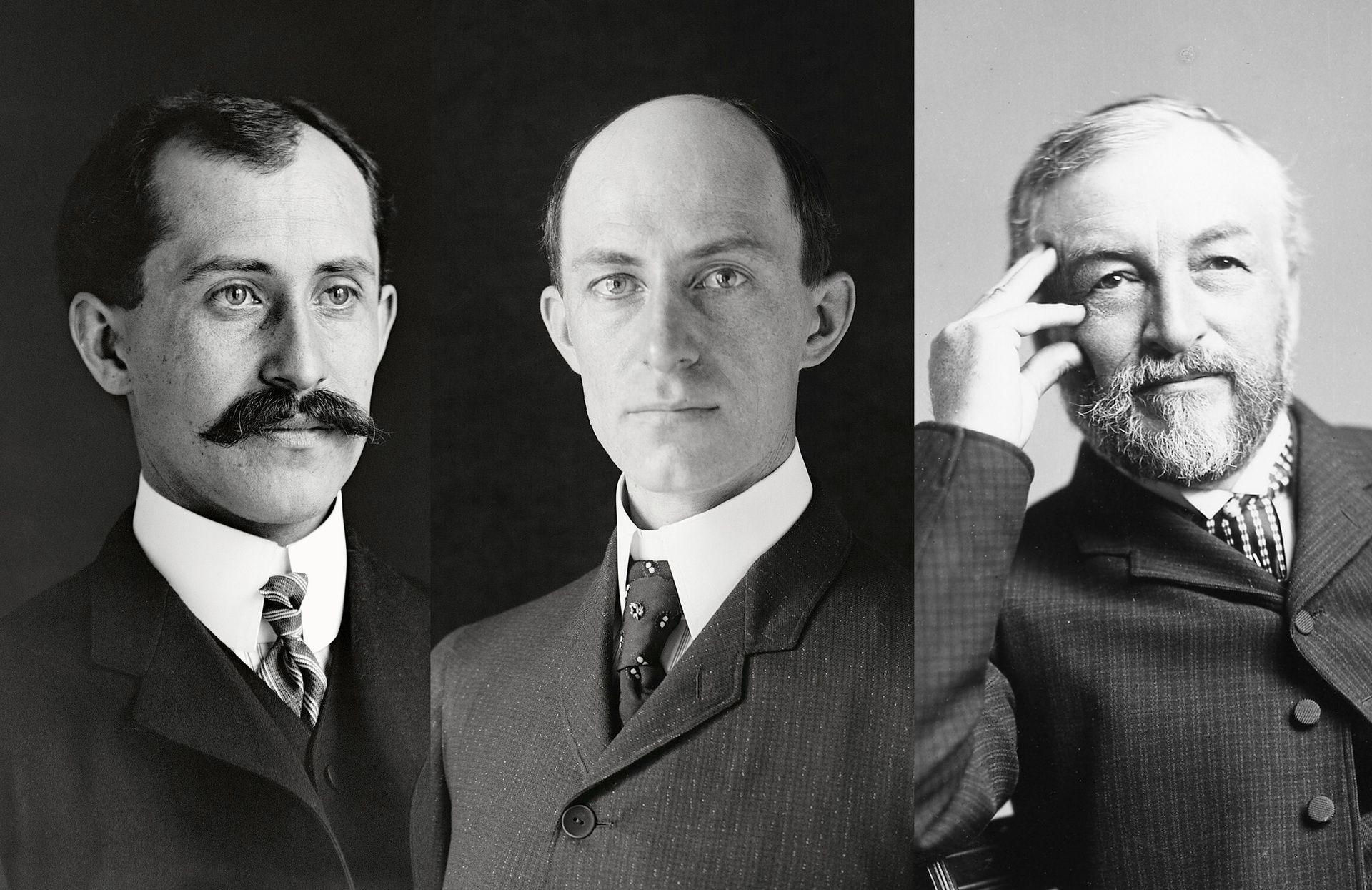

1898: The U.S. War Department funds Langley's aviation project with $50K (nearly $2 million in today's money). The Smithsonian puts in $20K. This makes it essentially the first government aerospace R&D program. So, Langley, the third secretary of the Smithsonian, is running what we'd recognize today as a venture-backed moonshot with heavyweight institutional backing for human-powered flight.

Think about the advantages: substantial funding, skilled machinists and instrument makers, the full resources of a government department and major institution, plus an experienced leader with scientific credibility. Everything you'd want for a breakthrough project.

1903: Langley's expensive aircraft crashes into the Potomac River. Twice. The pilot has to be rescued from the water both times. Then, the same week, two former bicycle mechanics succeed at Kitty Hawk with no outside funding, no institutional support, just methodical trial and error along with grit.

The government-funded effort with every advantage fails. The bootstrap effort succeeds.

The institutional response

Rather than acknowledge the failure and move on, the Smithsonian doubled down.

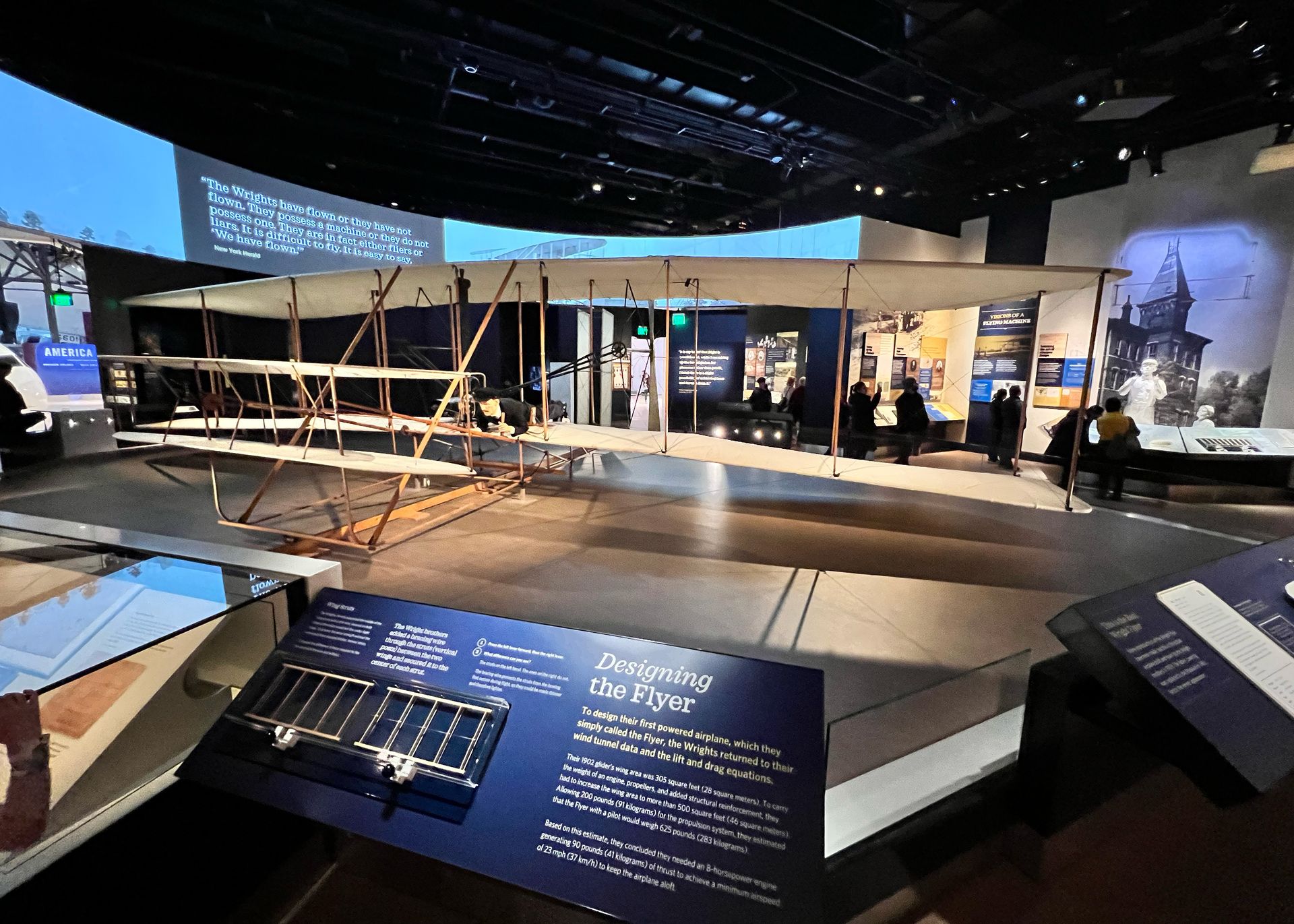

1914: Eleven years later, the Smithsonian secretly rebuilds Langley's crashed plane. They make major structural modifications — reducing wing area, strengthening the frame, upgrading the power train, adding floats, modifying the tail. They fly it for a few seconds and display it in their museum as the "first heavier-than-air machine capable of sustained flight."

This wasn't what happened in 1903. It was engineering a new aircraft and claiming the original could have flown.

1928: Orville Wright finds out about the deception and is furious. Instead of donating the original Wright Flyer to the Smithsonian, he sends it to the Science Museum in London in protest.

This is how one of the most important artifacts in American aviation history leaves the country because its logical home institution lied about who flew first.

Business challenge(s) got you spinning? We help unstick teams

The cascade effect

1942: After 14 years of public embarrassment, the Smithsonian admits to the modifications and retracts the story about Langley.

1948: To be able to display the Wright Flyer, the Smithsonian signs a legal agreement with Orville Wright's estate. The terms: if they ever recognize anyone else as achieving first powered flight, they lose the plane. The agreement is still in effect.

So a single moment of institutional face-saving in 1914 created a legal framework that still affects the way aviation history is told.

The Whitehead problem

Multiple people have claimed powered flight before 1903, including Gustave Whitehead in Connecticut (1901). There were witnesses. Newspaper coverage. The evidence isn't definitive — no clear photographs exist, witness accounts came later and sometimes contradict each other. Even Whitehead's wife said she never saw him fly, though she quoted him saying "Mama, we went up!" after his purported August 1901 flight.

Many mainstream aviation historians have reasons to dismiss the Whitehead claims. But the state of Connecticut officially recognizes Whitehead as first in flight. And the Smithsonian legally cannot, regardless of what evidence might surface. Unless they want the Wright Flyer to go elsewhere.

A photo from the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum of the Wright Flyer, taken in Jan 2023

What this teaches us about positioning and innovation history

This isn't really a story about who flew first. It's about how institutions shape which stories survive and how they get told.

The Smithsonian's 1914 lie was meant to protect their reputation after a failed project. It created a 30-year legal battle that ended with a contract that may prevent objective evaluation of historical evidence. Each attempt to fix the previous mistake created new constraints that were harder to escape. Since 1982, the most popular North Carolina license plates have said, "First in flight" with a blue outline of the Wright Flyer in the background.

I think this says something crucial about how innovation gets positioned in history. Institutions have the resources to shape narratives long after the fact. The Wright brothers succeeded, but they also benefited from having their story validated by the very institution that initially backed their competitor. Langley's failure got buried, then artificially resurrected, then buried again. And Whitehead's claims are largely unknown outside of Connecticut or aviation circles — along with many others.

Meanwhile, countless other innovators — particularly women and people of color — operated outside institutional frameworks entirely and often disappeared from the historical record altogether. For instance, Madam C.J. Walker built her cosmetics empire around the same time as these aviation experiments, becoming America's first self-made female millionaire through bootstrap entrepreneurship. But her innovations in chemistry and business rarely get mentioned alongside the "great inventors" of the time.

The positioning lesson: proximity to institutional power often determines which innovations get remembered, not just their objective merit. To circle back to the initial quote, the Wright brothers weren't aviation experts who got certified to fly. They were curious problem-solvers who created the field that eventually created the credentials.

Expertise follows innovation more often than it precedes it. But institutions can have massive impact on how that sequence gets remembered and taught.

This matters when we're building today's innovation narratives. Who gets credit? Which failures get acknowledged versus buried? Because the stories we tell about past innovation influence how we think about present opportunities.

Worth remembering when we're positioning the breakthroughs that will become tomorrow's "established facts."

Something else to consider

“I had to make my own living and my own opportunity. But I made it! Don't sit down and wait for the opportunities to come. Get up and make them.”

Coming from someone who built a cosmetics empire (Madam C) around the same time and became the first female self-made millionaire in America (so says the Guinness Book of World Records), I think this contrasts bootstrap entrepreneurship with waiting for institutional backing — the dynamic between the Wright brothers and Langley's well-funded project.

Expertise follows innovation more often than it precedes it. But institutions can have massive impact on how that sequence gets remembered and taught.

This matters when we're building today's innovation narratives. Who gets credit? Which failures get acknowledged versus buried? Because the stories we tell about past innovation influence how we think about present opportunities.

Worth remembering when we're positioning the breakthroughs that will become tomorrow's "established facts."

Until next time,

Skipper Chong Warson

Making product strategy and design work more human — and impactful

—

Do you have a hairy problem in your business that could benefit from outside thinking and support? Book an intro call with How This Works co